Color

Management in Adobe Photoshop® part 4:

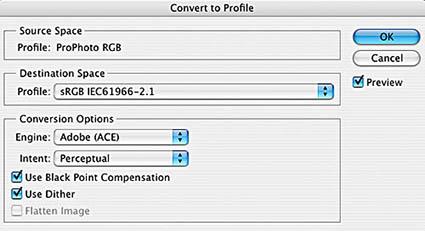

The Convert to Profile Dialog Box

(And What You Can Do With It)

With a clear understanding

of the differences between assign profile and convert to

profile, we can begin to talk about actually using these

concepts in Adobe Photoshop. If you do not have a clear

understanding of the distinction between the two, I

strongly suggest that you read or re-read the previous

section, “Assign Profile Versus Convert to

Profile”, because the rest of this series assumes

familiarity with these concepts. Assign profile and convert

to profile can be accessed directly from the top menu in

Photoshop. In Photoshop CS and earlier, this was

accomplished by selecting from the top menu Image>

Mode> Convert to profile or Assign Profile. For CS 2 and

3, choose Edit> Assign or Convert to Profile. The

convert to profile dialog looks like this:

Taking the options in this

box from the top, we first see the origin space. This

cannot be changed because it refers to the color space or

profile that the image is in (or is assumed to be in.) Next

is the destination space, which is where you want to

convert your image to. Any color space or profile visible

to Photoshop is available through the destination space

pull-down menu.

Conversion options are next. These include the

“engine” or color management module (CMM) used

to perform the conversion. The CMM is essentially an

interchangeable calculator used to translate the color

meaning. In the early days of color management, some

companies “tuned” their CMMs to take advantage

of special “secret sauce” information in the

profiles created by their software. This was in direct

conflict with the platform-independent interoperability

that was a key goal of the ICC, so CMMs that favored a

specific vendor were relatively short-lived. Today few

profiling software companies bother to create separate

CMMs, and Adobe’s Ace Engine has always been one of

the best. So unless you have a specific reason to use

another CMM, such as a legacy Kodak or Heidelberg profile,

Adobe ACE is a better choice than the “operating

system freebie” CMMs.

Next down the dialog box is the rendering intent, which is

just called “intent” in some versions.

Rendering intent mainly tells the CMM how to deal with

“out of gamut” colors; colors that exist in the

source space but cannot be coded directly into the

destination. Depending on the intent chosen, some in gamut

colors are usually affected also. It should be noted that

when converting into any of the currently used

“editing” color spaces such as sRGB, Adobe 98,

ProPhoto etc., the only intent currently supported is

relative colorimetric. Photoshop CS1 and earlier allowed

absolute colorimetric as well, but this was rarely a useful

option. Adobe decided that absolute was being chosen by

mistake most of the time that it was used and discontinued

the option for CS2 and later. So while the other rendering

intent choices show up in the menu for these spaces, if you

choose one of them and click the preview box you will see

that they have no effect.

Rendering intent only becomes a real decision when

converting to an output profile such as a printer profile.

To give a brief overview of the choices, I will begin with

the two most frequently used intents, perceptual and

relative colorimetric. The remaining two intents,

saturation and absolute colorimetric, are used less

frequently and only in special situations. They will be

discussed in-depth in the “All About Rendering

Intents” (coming soon) section of the website.

Perceptual maps all possible colors (from LAB- it knows

nothing about the size of your source profile) to in gamut

ones while maintaining smooth transitions to the colors

that would have been in gamut any way. This has the

advantage of preserving smooth transitions and maintaining

relative color relationships, but tends to affect a more

significant amount of in gamut color than the other

intents. It is widely used for photographic images, where

relative color relationships are often more important than

absolute color accuracy. To maintain the relationship

between in and out of gamut colors however, severe

compression is applied to almost all color values,

including in gamut ones. This means that some saturated

colors that could be reproduced in the destination get

somewhat de-saturated. This happens even when no colors in

the source would be out of gamut.

Relative colorimetric attempts to leave all in gamut colors

unchanged, and map out of gamut colors to the nearest in

gamut choice. This makes it an excellent choice if all of

the source colors exist in the destination space. If this

is not the case however, then the transition to the

formerly out of gamut colors can be abrupt. A whole range

of out of gamut color may be translated to the single

nearest destination color. We call this “saturation

clipping” because the end points of a color range are

clipped off, or stop becoming more saturated. This changes

the relationships between colors and in extreme cases can

lead to flat blobs of saturated colors where a gradation

would otherwise be. Sometimes this is objectionable, other

times it is hardly noticeable.

The choice between perceptual and relative colorimetric is

dependent on image, profile and intended use of the

converted file. As a general rule, perceptual is often best

for translating photographic images into a small printer

profile because of it’s ability to scale out of gamut

ranges and maintain color relationships. For converting

photographic images to large gamut printer profiles, and

for accurate color conversion of non-photographic flat

color graphics, relative colorimetric is often the better

choice. There is no “one-size-fits-all” answer

here, so this is where the “preview” check box

can be pretty useful. Just keep in mind that you are

viewing the color change in the file “through”

your monitor profile. This means that if any color ranges

lie outside of your monitor’s gamut, you will be

unable to see a change even if it takes place. This usually

does not present much of a problem, and clicking preview on

and off is generally a very good way to ascertain the

effects of a profile conversion.

Next in the convert to dialog box is the option of black

point compensation. Some profiles translate their darkest

possible value directly into the space they are converted

into. This means that if you are going from an offset press

profile, which is typically not capable of producing a very

deep black, to a device profile with darker blacks, the

darkest value in the image keep the same appearance as they

had in the more limited profile. Thus you lose some

advantages of the second device by not being able to print

the darker black that it is capable of printing. Not all

profiles translate black in this way, and the difference is

due to ambiguity in the original ICC specification. Black

point compensation is an Adobe proprietary solution which

when turned on will always map the darkest possible value

in source to the darkest possible value in the destination.

Unless you are trying to duplicate a workflow that does not

offer the ability to use black point compensation, it is

always best to map black using this option by checking the

box.

Finally we have “use dither” and “flatten

image”. Use dither introduces a tiny amount of noise

to the image in the conversion process. It seems

counterintuitive, but this is actually desirable for most

photographic images. This is because any profile or color

space conversion, especially 8-bit ones, will have at least

a slight amount of rounding errors in the mathematical

conversion. The resulting loss of data, which is usually

small, is called quantization. It is almost never

noticeable on textured parts of an image, but sometimes can

be visible in very smooth gradations (like a cloudless sky)

as slight “posterization” or

“banding”. The minimal noise introduced by the

use dither control will ensure that you do not see this

banding as the result of a single transform into a normal

profile. So if you have a tonal or photographic image,

checking use dither is the way to go. If your image is a

flat graphic creation that has no gradients however, then

you probably don’t want even the slight amount of

noise that this control introduces and you should leave the

box unchecked.

The flatten control will collapse all of your Photoshop

layers before making the profile or color space conversion.

Since some layer options and blending modes are dependent

on the profile or space in use at the time, flattening

before conversion stands the best chance of keeping the

appearance of a file as unchanged as possible. Of course,

you lose the advantage of editing any of the pre-existing

layers going forward. If this presents problems, try the

conversion and use Edit>undo to toggle back and forth to

evaluate the visual difference. You must use this method

for evaluation because the preview checkbox does not

preview the effects of unchecking the flatten box. In other

words, preview will always show you the result of

flattening before the conversion.

So what can you actually do with the convert to profile

dialog? Some very useful things, including:

• Convert to another color space.

You could use convert to

profile to change a copy of your digital camera RAW

conversion in ProPhoto into a smaller space like sRGB to

email to your friends. (Most low-end image viewers assume

that everything is in sRGB) Or you could convert an sRGB

file into a larger space like ProPhoto to achieve more

saturated colors than are possible in sRGB. Please note

that if you are doing this, the conversion alone to the

larger space does not make the color in the file any more

saturated. The purpose of convert to profile is to

translate to the destination color space without changing

the color at all. To saturate the colors beyond those

available in a small space you must convert to a larger

space and then use adjustment controls like

Image>Adjust>Hue and Saturation.

• Convert to a

printer profile for printing. If you have a custom profile for your

printer, paper and ink combination, this is where you would

use it. The best approach is usually to convert to profile

and print from Photoshop. Make sure that color management

is turned off in the printer driver; you may have to

consult your printer manual for this. For an excellent

tutorial on printing with Photoshop, click

here. Note that you would not want to save

the converted version as your only copy of the file

because after the conversion it will only contain colors

that are printable under that condition, i.e. that paper

on that printer with that ink. This would limit your

ability to use a more capable printing condition and

profile in the future, so if you need to save the

converted version, save it as a copy.

• Convert to another color

mode. Most people use

Image> Mode> and choose the color mode to accomplish

this. Convert to profile can be used to convert between

most of the commonly used color modes with much greater

control. For instance, if Image> Mode> is used, then

the default working space for that mode from your Photoshop

color settings is always used as the destination space for

that mode. So if you were sending a job to a print shop

that used a profiled CMYK, press, it might seem to make

sense to use Image> Mode> to convert to CMYK and then

convert to the press profile. However, this would involve

an unnecessary conversion to your CMYK working space that

would introduce another level of quantization and could

cause additional problems with black generation. Using

convert to profile to go straight from RGB to the CMYK

press profile would be a better choice. In addition

Image> Mode> also uses your Photoshop color setting

defaults for rendering intent and dither setting. The only

way to independently control these variables for each mode

conversion is to use the convert to profile

option.

Go to part 5: The Assign

Profile Dialog Box

Return to The

Educational Information home

page